by Dennis Kriesel

A huge thanks to Dennis Kriesel of the Eclectic Gamers Podcast for this interesting article! Check out the Eclectic Gamers Podcast here, and their Facebook page here!

Introduction

In the world of pinball, particularly modern pinball, there tends to be a relatively consistent layout to the lower playfield. This structure of design is commonly referred to as the “Italian Bottom”, but a lot of people do not fully understand what that entails. Indeed, individual definitions can vary wildly, with some ascribing very specific characteristics for the term far beyond original usage (including pinball designers!).

So, what is an Italian Bottom really? According to Bally pinball designer Greg Kmiec (who discussed the conception in IPDB’s Paragon entry) in regards to his game Paragon and the design changes made for the European market, “It was relayed to Bally that the foreign player preferred one return lane on each side at the bottom of the game that “returned” the pinball to the flippers for a playfield skill shot. This type of design became known within the industry as the “Italian Bottom.” It was used extensively then throughout the industry and is still in use today.” Kmiec explained how the European markets indicated their players wanted ways to trap up to talk, drink, and attempt to make skillful shots.

Paragon’s European variant was hardly the first game with an Italian Bottom, and as players today know it is, by far, the most common layout approach. So, here are the key elements:

- One return lane (often called an inlane) on each side to feed the lower flippers

- An outlane (drain) on each side

- The nature of the return lane must support easy trapping (e.g., an upper flipper can work, but not if it creates a hole when the lower flipper is engaged, a la the U.S. version of Paragon).

One can get even more particular, such as that originally wireform returns were used in Italian Bottom designs (other materials are technically modifications away from original purity, something Steve Ritchie discussed in a special issue of Pinball Magazine), but the above two elements are the ones central to a hobbyist understanding the concept. The use of outlanes is noted as a sub-section to the first element. Kmiec did not define it this way specifically when explaining Paragon, but Ritchie does in his explanation and it is consistent with the three flipper version of Paragon (though one might view the left outlane is less of a lane and more of a gaping hole, but such is the price of the Beast’s Lair) and other known Italian Bottom pinball machines of the era. Kmiec likely meant to imply it (if there is a return lane there is also a lane that does not return; outlanes are very common throughout flipper pinball’s history and often a staple of non-Italian Bottom games).

Today, a lot of people interpret an entire symmetrical lower playfield, from outlane to outlane, as being the Italian Bottom, but really things like identically placed/sized slingshots abutting the start of the lanes are not a part of the definition because they don’t really relate to the feed/trap goal the Italian Bottom references. Such aspects are typical with an Italian Bottom but are not a mandate and are better identified as elements of the modern standardized lower layout. Indeed, Kmiec’s discussion of the European (three-flipper) version of Paragon as an Italian Bottom shows how symmetry in other lower features was not a part of the equation (the slings are in completely different positions).

As such, this article will provide a series of examples, carved into four classifications for comparison purposes:

- The standard configuration (traditional Italian Bottoms with standardized lower layout elements)

- Non-traditional Italian Bottoms with standardized lower layout elements

- Italian Bottoms (traditional or non-traditional) with an atypical lower layout

- Non-Italian Bottoms

The standard configuration (Traditional Italian Bottoms with Standardized Lower Layout Elements)

This is the modern, standard configuration of the lower playfield. These pinball machines have stereotypical lower playfield configurations (as noted above, from outlane to outlane there is a basic mirrored look in regards to slingshot positioning, with said slings up against the start of the various lanes; lane quantity may be asymmetrical and still meet the definition of a standardized lower layout but such cases will be dealt with as non-traditional Italian Bottoms later in the article). Almost anyone who has heard the term “Italian Bottom” would apply it to these games, and they would be right to do so. Some people circumscribe Italian Bottom to only mean standard configuration pins, which is inaccurate. That said, the sameness across these lower sections of standard configuration games are obvious via photographs.

Firepower (Williams 1980) adheres to the traditional Italian philosophy (two inlanes and outlanes, one on each side) with ball guides from the inlanes feeding to the flippers. The slings (aside from art) are identical mirrors. The only difference noticeable is the guide separator for the inlane and outlane on the left is a different material than on the right (possibly to accommodate the left kick-back feature and force it applies), but this is not enough difference to consider the lower layout an atypical variant.

Jacks to Open (Gottlieb 1984) offers all the core tenets of traditional Italian Bottom design (an inlane/outlane configuration on both sides with wire ball guides feeding to the flippers) along with mirrored sling placement to standardize the lower playfield. There are a couple interesting differences, however. First, the slings are passive (no kickers) but that holds no impact on the look or position so the standardized lower layout is maintained. Also, the inlane guides on both sides have sizable gaps to allow the ball to go between the inlane and the outlane. This makes trapping a trickier matter than if these gaps did not exist (alley passing is high risk and depending on momentum the bottom corner of the sling can actually bounce the ball back towards the outlane even on a clean inline feed) but technically this is no violation of the traditional Italian Bottom concept (there’s still plenty of ball guide for feeding the flippers and trapping up) and all is done within the constraints of a standardized layout.

Moving into the modern era one can see how strongly the Italian Bottom with a standard lower layout has taken hold. With Star Trek (Stern 2013) the inlane on each side is cleanly and uniformly separated from the outlane. Long ball guides supply the flippers. Identical slings closely hug the inlane channels. A prototypical Italian Bottom and standardized lower playfield.

The Walking Dead (Stern 2014) has a different designer than Star Trek but you would never know it from the lower playfield. Once again, an inlane on both sides cleanly and generously separates from the outlanes. Smooth flipper feeds from the inlanes. Identical slings abut each inlane. A textbook example.

Changing to another designer and another company, Total Nuclear Annihilation (Spooky 2017) was seen by many as a throw-back design with its single-level playfield, but the lower section follows all the rules of a traditional Italian Bottom (one inlane and outlane on each side with ball guides to the flippers). The rest of the lower section is also of the standard variety (identical mirrored slings, closely against the inlanes), though the game’s style changes once you get above this lower third section.

There are scores of other examples. But even though these are all obviously Italian Bottom games, one must remember that an Italian Bottom is quite possible even if the rest of the elements are not in the standard configuration. But first, it would be good to examine adjustments to the traditional Italian Bottom itself.

Non-Traditional Italian Bottoms with Standardized Lower Layout Elements

These pins typically deviate by having more than one return lane or some unique differences in outlane(s). In other words, there is some sort of asymmetry to the Italian Bottom but the game still achieves the stated goals of an Italian Bottom by feeding the lower flippers via a return lane and promoting easy trapping. Here we are keeping with the rest of the lower third of the playfield remaining standardized (the typical sling approach). Non-traditional Italian Bottoms deviate from Kmiec’s definition on a technicality but still meet all the objectives of the design. Nonetheless, the deviation is significant enough to warrant a slightly different classification.

Pat Lawlor’s game Dialed In! (Jersey Jack 2017) is a great example of the non-traditional Italian bottom. The right side adheres to the traditional approach, but an additional inlane exists on left side. The rest of the lower playfield is completely standardized to the modern approach.

Judge Dredd (Bally 1993) is another good example of this style. The left side in this case holds one inlane while the right side has two. This widebody game accommodates a far-left missile launch area the ball can feed into but this is beside and distinctly separate from the rest of the lower playfield (recall that the standardized assessment is the lower third from outlane to outlane, and this addition is outside of that examination area).

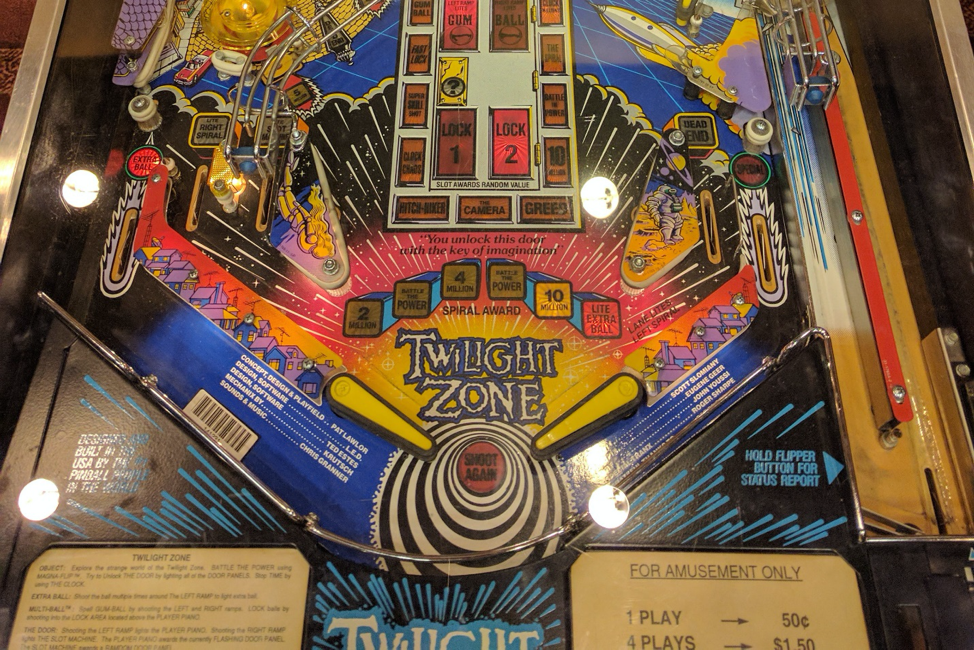

Moving to another Lawlor design, Twilight Zone (Bally 1993) is a widebody but follows a non-traditional Italian Bottom approach similar to the Dialed In! pin. The left side has two inlanes serving the flipper, the right side has one, and everything else is what players anticipate in terms of standardized lower playfield design.

Italian Bottoms (Traditional or Non-Traditional) with an Atypical Lower Layout

This classification is interesting and technically could be carved into two categories (if one wanted to further segregate the traditional Italian Bottom formats from the non-traditional styles). However, the main aspect is the atypical (non-standardized) lower playfield layouts while still being an Italian Bottom. This is a category that often confuses the modern player, with many people focusing on the atypical elements and assuming the game is not actually an Italian Bottom. The following lower playfields adhere to the rules of the Italian Bottom while also deviating substantially from the standardized lower layout normally seen today.

Buck Rogers (Gottlieb 1980) is a nice example of this category. The bottom is clearly Italian (traditional at that) but there is one notable difference: the slingshots are not mirror images. The left slingshot is quite a bit larger than the right slingshot. In fact, the right slingshot is passive (no kicker) while the left is active. Visually, the slingshot differences catch the eye immediately and make the lower playfield feel different. It is different, but it is still an Italian Bottom.

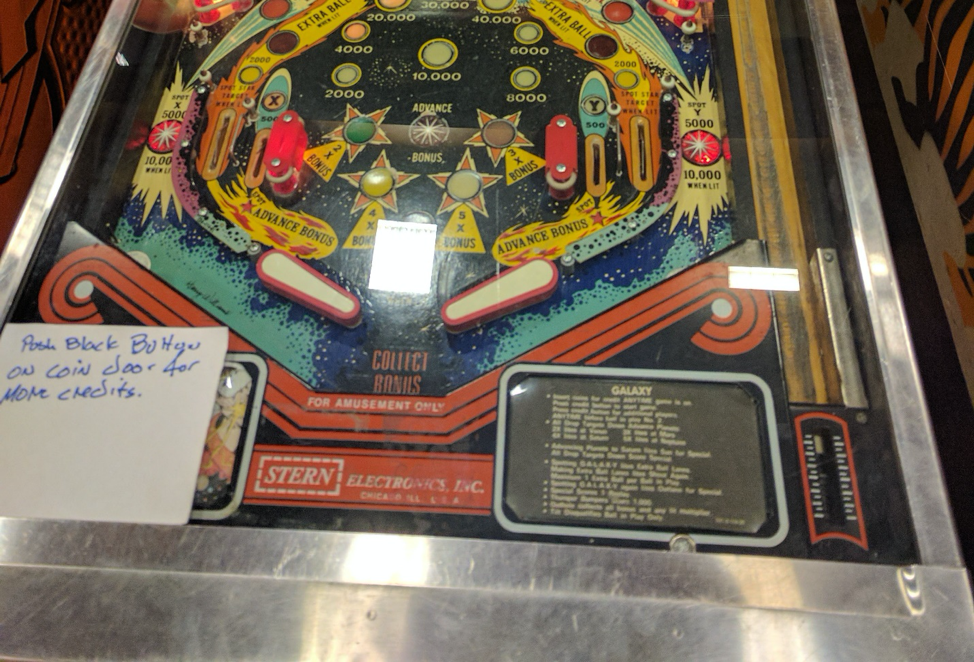

Harry Williams designed a game called Galaxy (Stern 1980) which is a pretty interesting Italian Bottom. Each side’s flipper is served by two inlanes and a single outlane (so this is a non-traditional Italian Bottom). The lower playfield is also mirrored. But it’s still atypical because of the slingshots. There are lane guides with rubber rings approximately where a player would expect to see slings. The game does have slingshots, further up the playfield, but obviously this placement decision creates an atypical lower layout while still maintaining an Italian Bottom.

Hoops (Gottlieb 1991), a competitive favorite, is another example of an Italian Bottom (traditional) in an atypical lower playfield. Much like Buck Rogers the sling sizing is notably different. The left sling is much taller than the right sling, and that provides a great deal of asymmetrical side-to-side action around the flippers. Unlike Buck Rogers, both slings are active, however the left sling has two switches which can activate the kicker (as most modern slings do) whereas the right sling only has one such switch. In addition, while the inlanes are traditional Italian they are shaped differently (in part to accommodate those sling placements), with the right inlane being in the more traditional vertical alignment and the left inlane angled more (resulting in a lot of high-speed returns to that flipper).

Soon-to-be produced Rick and Morty (Spooky 2020) serves as a very modern example. The game is an Italian Bottom (traditional) with an inlane and outlane on each side (the lane guide on the left inlane even protects from the pop bumper so the feeds are going to be quite stable) and guides to the flippers. Obviously the lower playfield itself is an atypical variant of a type not seen in quite a while: a pop bumper plus slingshot combination. While the purpose of both devices is similar the actual play experience of a pop bumper is significantly different than a slingshot, and thus an asymmetrical player experience results from the design decision (while still, quite clearly, being an Italian Bottom).

Non-Italian Bottoms

This article has walked through a lot of games with Italian Bottoms. There are, of course, games that do not adhere to the Italian Bottom approach (especially from the electromechanical era) and thus what they look like can vary quite a bit. This article will walk through a few examples.

On first glance, Sharpshooter (Game Plan 1979) may appear to be an Italian Bottom. The left side looks traditional (one in-lane). But the right side lacks an outlane, so the definition is no longer met. In addition, the right side does not have a true return lane as the path to the flipper is all rubber. As such, the whole right side is full of bounce and a lack of control. Compared to Rick and Morty in the prior section one can easily see the difference in the Italian Bottom approach versus a non-Italian Bottom approach; even though both lower sections are atypical in an almost mirrored way the differences between the two pins are stark.

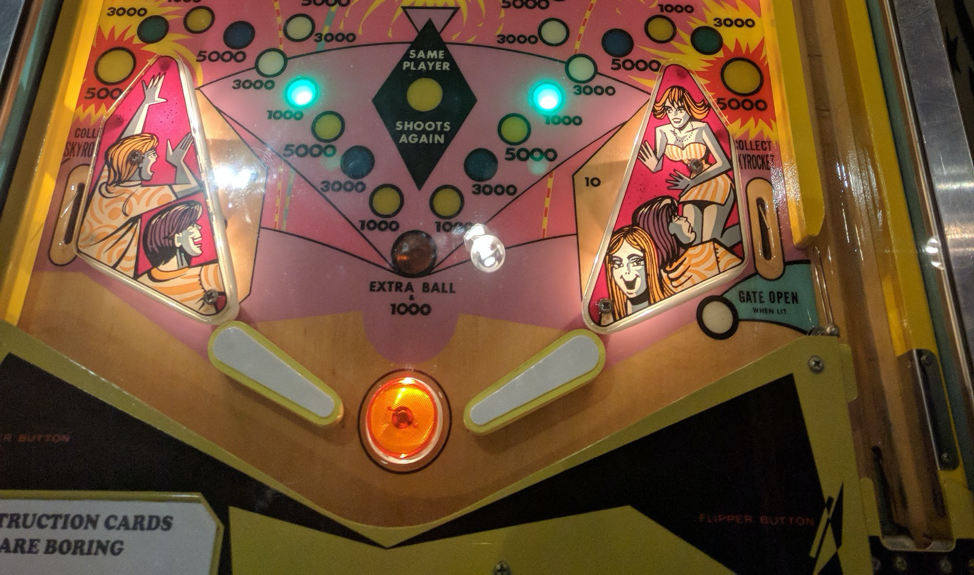

Skyrocket (Bally 1971) is perhaps an easier to follow example. No return lanes exist at all, so it clearly is not an Italian Bottom. The game also does not promote trapping up, as the slingshots are aligned up against the flippers. Yes, it is possible to trap up, but not in the convenient way an Italian Bottom would promote.

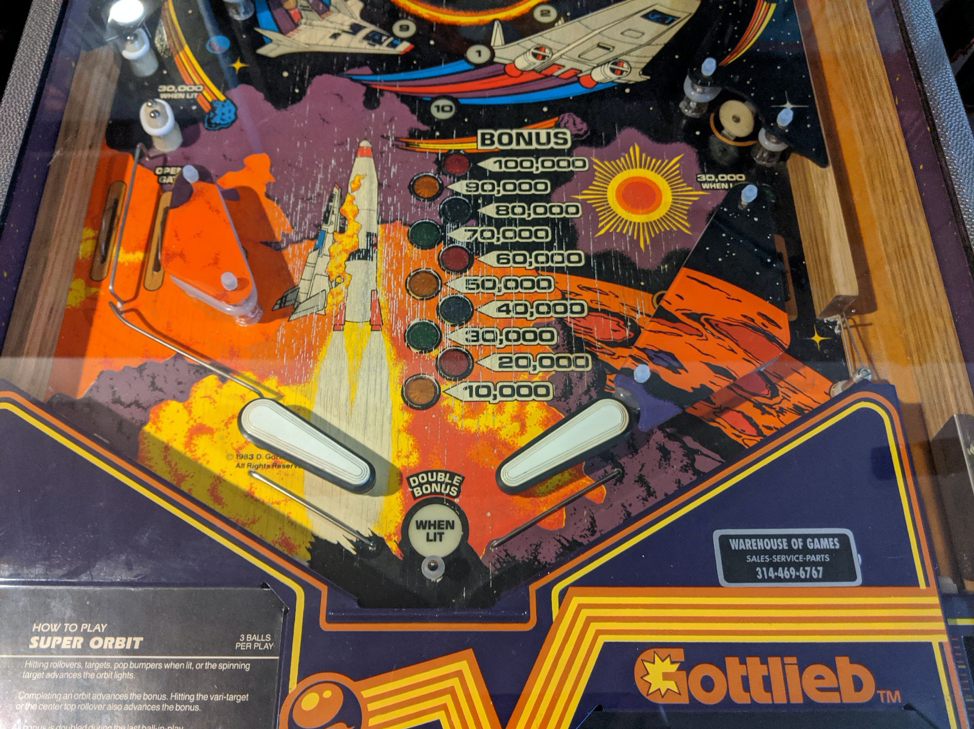

Super Orbit (Gottlieb 1983) is a fun example as it is something of a hodge-podge of the prior two non-Italian Bottom games reviewed. Much like Sharpshooter, the left side appears to follow a traditional Italian Bottom approach. Much like Skyrocket, the right side has a slingshot right up against the flipper. So, this is not an Italian Bottom, because the right side lacks a return lane and the right side also does not promote trapping up. The lower playfield is also quite atypical because of the sling sizes and placements (the left sling on Super Orbit is passive, the right is active). The right outlane does have a gate that can return to the shooter lane, but an Italian Bottom has a return lane to a flipper and thus Super Orbit is in clear violation (even discounting the trap difficulty on the right flipper).

Conclusion

The key takeaway is Italian Bottom is a term that only refers to layouts with return lanes/outlanes with a return that encourages trapping the ball. That is all. Almost all pinball machines today are Italian Bottoms because the modern standardized lower playfield includes those elements, but also includes more specific aspects (namely symmetrical slings up against the start of the various lanes). As such, pins with a modification to the standardized lower third may still actually be Italian Bottom games and thus it would be a misuse of the term to say they are not. The evolution of the lower portion of the pinball playfield is a fascinating journey in and of itself. Hopefully this article helped better explain the actual concept of the Italian Bottom and what purpose it seeks to serve.